Isidor Buchmann |

Isidor Buchmann is the founder and CEO of Cadex Electronics Inc. He is the author of www.BatteryUniversity.com, has written award-winning articles including the best-selling book "Batteries in a Portable World: A Handbook on Rechargeable Batteries for Non-Engineers," now in its fourth edition. For three decades, Buchmann has studied the behaviour of rechargeable batteries in practical, everyday applications.

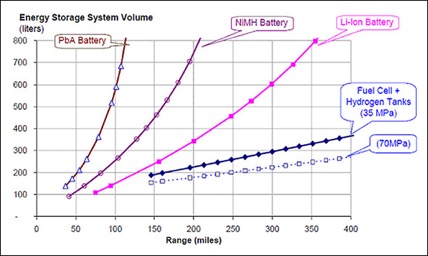

The fuel cell as a propulsion system is, in many ways, superior to a battery because it needs to carry less energy storage by weight and volume compared to a vehicle propelled by batteries only. Figure 1 illustrates the practical driving range of a vehicle powered by a fuel cell (FC) compared to lead acid, NiMH and Li-ion batteries.

Fuel options |

Although the fuel cell assumes the duty of the internal combustion engine (ICE) in a vehicle, poor response time and a weak power band make on-board batteries necessary. In this respect, the FC car resembles an electric vehicle (EV) with an on-board charger that keeps the batteries charged. This results in short cycles that reduces battery stress over the EV; a propulsion system that bears a resemblance to the HEV.

The FC of a mid-sized car generates around 85 kW (114 hp.) to charge the 18 kWh on-board battery and drive the electric motor. On start-up, the vehicle relies fully on the battery; the fuel cell only contributes after reaching a steady state in 5-30 seconds. During the warm-up period, the battery must also deliver power to activate the air compressor and pumps. Once warm, the FC provides enough power for cruising; however, during acceleration, passing and hill-climbing, both the FC and battery provide throttle power. Braking delivers kinetic energy to the battery.

Hydrogen costs about twice as much as gasoline, but the higher efficiency of the FC compared to the ICE in converting fuel to energy brings both systems on par. The FC has the added benefit of producing less greenhouse gas than the ICE.

Hydrogen is commonly derived from natural gas. Folks might ask, "Why not burn natural gas directly in the ICE instead of converting it to hydrogen through a reformer and then transforming it to electricity in a fuel cell to feed the electric motors?" The answer is efficiency. Burning natural gas in a combustion turbine to produce electricity has an efficiency factor of only 26-32% while a fuel cell is 35-50% efficient. That said, the machinery required to support the FC is costlier and requires more maintenance than a simple burning process.

To complicate matters further, building a hydrogen infrastructure is expensive. A refueling station capable of reforming natural gas to hydrogen to support 2,300 vehicles costs over USD2 million, or USD870 per vehicle. In comparison, a Level 2 charging outlet to charge EVs can easily be installed by connecting to the existing electric grid. The benefit with FC is a quick refill similar to filling a tank with liquid fuel.

Durability and cost are further deterrents for the FC, but improvements are being made. The service life of an FC-powered car has doubled from 1,000 hours to 2,000 hours. The target for 2015 onwards is 5,000 hours, or a vehicle life of 240,000 km.

A further challenge is vehicle cost as the fuel cell is more expensive to build than an ICE. As a guideline, a FC vehicle is more expensive than a plug-in hybrid, and the plug-in hybrid is dearer than a gasoline-powered vehicle. With low fuel prices, alternative propulsion systems are difficult to justify on cost alone and the environmental benefits must be considered. Japan is making renewed efforts with FC propulsion to offer an alternative to the ICE and the EV. Toyota plans to phase out the ICE by 2050 and other vehicle makers are observing the trend.